Bronx Music History

The Bronx’s economic and physical development grew and changed in tandem with what was taking place in the arts and music, as well as new and emerging entertainment trends happening throughout the borough and the City at large. The Bronx’s building boom of housing, elevated train lines, and theaters in the early decades of the 20th century would create the foundation of a diverse dynamic music scene going into the 21st century. Successive waves of migration—Germans, Jews, Puerto Ricans, Irish, West Indian, African American, Garifuna, West African, and Bangladeshi--would add rhythms and languages to the soundscape. Some of these would merge to form new genres. From the “Piano Capital of the U.S.” to “El Condado de la Salsa” to its nickname as the “birthplace of hip hop”; through crises ranging from housing loss, fires and gentrification, the music has been a reflection of the people who have made the borough their home.

Between 1880 and 1930, the Bronx was one of the fastest growing urban areas in the world. This literally sets the stage for the music that would come out of the borough. During the middle of the 19th century, many German immigrants migrated to the Bronx as they moved from the crowded Lower East Side, to the open farmland of the South Bronx in neighborhoods like Melrose. The crucial early turning point for Bronx growth was the construction of the Third Avenue Bronx extension of the Manhattan Second Avenue elevated line in 1886. The addition of elevated train lines and subways and increased building activity left dense urban areas in their wake.

Around this time, the piano manufacturing industry took hold in the southern areas of the Bronx. According to Bronx historian Lloyd Ultan, the southernmost Bronx neighborhoods of Mott Haven and Port Morris became the “Piano Capital of the United States.” (In 2015, real estate developers wishing to cash in on some Bronx “authenticity” tried – and failed - to rename the area near the Third Avenue Bridge as “The Piano District”).

At the same time, New York City became the epicenter for many Latin music trends. Tango, which originated in the dockside communities in Buenos Aires in the late 19th century, was introduced to NYC in 1913 with the Broadway musical comedy called The Sunshine Girl. Within months the tango was a national mania.

By the 1920s, the borough was home to 700,000 people, enough to make it the 9th largest city in the United States, if it had been a separate municipality. A New York Times article from June 11th, 1921 comments upon all the recent theater construction in the borough:

The recent growth in the residential section of the East Bronx is perhaps best illustrated by the steady increase in the number of theatres which have been built in that part of the city within the last few years.

The late 1920s and early 1930s also saw the rise of theater shows. Meanwhile, New York City is becoming the world’s capital for all things related to the recording industry: recording, sheet music, piano rolls, and the radio. By the late 1920s, though the piano factories were for the most part closed, the Bronx was known far and wide as the home of the New York Yankees, the Bronx Zoo, and Fordham University.

Musically, the Puerto Rican community, which would later play a major role in the growth of mambo and salsa, were now altering the City’s soundscape with the traditional narrative ballad from the island called plena. So as Puerto Ricans were migrating here, the musicians among them found a welcoming environment in which to perform music.

*Photo Credit: Article from Brooklyn Eagle 10/7/13

The 1930s saw a new round of subway and infrastructure construction. From a musical perspective, while the first decades of the 20th century saw the mainstream dipping its toes into Latin music during the tango craze, next Cuban music took hold in New York City and lasted into the next century. The Harlem Renaissance, which coincided with the Negritude movement in the Caribbean and lasted from the Roaring Twenties to the 1930s, also played a part in the popularity of Afro-Caribbean music. It sought to celebrate an African past and the New World experience shaped by slavery and struggle. In 1930, Don Azpiazu’s Havana Casino Orchestra performed at the RKO Palace Theater on Broadway and 46th St. They played “El Manicero” (“The Peanut Vendor”) and introduced the public to a type of Latin music with a more complex African element than that of the tango, the Cuban son.

Following World War II there were massive migrations to New York City of Puerto Ricans from the island and African-Americans from the South. At the same time, Bronx neighborhoods began to see major shifts. According to historian Mark Naison, by the late 1940s, Morrisania, once a largely Jewish, working class section of the Bronx had become the borough’s largest African-American neighborhood. The first generation of Blacks who moved to Morrisania from Harlem also included a large contingent of West Indians. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Morris High School was perhaps the single most-integrated secondary school in the United States. In 1940, Machito’s Afro-Cubans made their debut at the Park Plaza Ballroom in East Harlem—fusing big band jazz music together with Afro-Cuban rhythms. By 1949 mambo had broken out of Manhattan and was danced in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

The 1950s saw more new genres emerging in NYC, with the Bronx at the vanguard. Long before hip hop became the music of a generation, doo wop harmonies were part of the Bronx’s soundscape. A group of girls from the Bronx River Houses who went to nearby James Monroe High School and called themselves the Desires’ Debs met a young songwriter, Ronnie Mack, who also lived at the Bronx River Houses. Mack wrote a song called “He’s So Fine” (recognizable by the repeated line “doo lang, doo lang”), and the Desires’ Debs changed their name to the Chiffons and recorded his song. It became an immediate hit.

Morris High School on Boston Road in Morrisania was another hub of doo wop and R&B music. It was in its hallways that the Chords rehearsed their harmonies and would later record their hit “Sh-Boom.” Down the street at St. Anthony of Padua Catholic School, Arlene Smith organized her friends into a group called The Chantels and recorded their hit “Maybe.” A block away from “the Home of Mambo,” the Palladium in Manhattan, was the jazz club Birdland, where Latin music and jazz mingled. Birdland was also the venue where jazz’s avant garde performed, such as the leaders of the new genre be-bop: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane.

The Bronx at this time has its own jazz scene along Boston Road, and not too far away, be-bop pianist Elmo Hope lived on Lyman Place near another be-bop pioneer, pianist Thelonius Monk, who lived there for a short time. Be-bop found a home at the 845 Club located at 845 Prospect Avenue, where one could see be-bop legends like Dizzy Gillespie and Art Blakey perform.

*Photo Credit: Justo A. Marti, Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY.

Soon a plethora of problems began emerging in the Bronx. Decrepit buildings were left to burn, while neighborhoods like Charlotte Street, once a symbol of working class aspirations, deteriorated. At the same time that the Bronx was changing, so was the music scene. The Palladium closed in 1966, signaling the end of an era: in the Bronx, boxer Carlos Ortiz’s Club Tropicoro closed, along with the borough’s famed Tropicana. While mambo was losing its venues, the late 1960s saw the rise of Latin bugalú, which was popular with young Latinos. Bugalú, a playful fusion of Latin, jazz and R&B musical genres with English and Spanish lyrics, was an interplay between Black and Latino cultures, as they lived side by side in neighborhoods throughout the City. Some of its major contributors came from the Bronx, including Pete Rodríguez (“I Like It Like That”) and Hector Rivera (“At the Party”).

The borough’s social ills only worsened. In 1976, the worst year for the fires, the South Bronx reported over 35,000 fires of all kinds. Engine 82, Ladder 21 on Intervale Avenue became the busiest firehouse in the nation. Outside of war, there is very little precedent for the kind of destruction that took place in the neighborhoods that became known as the South Bronx. Latin music once again went through a transition. What became known as “salsa”-- the same Afro-Cuban based music as mambo but with urban, grittier instrumentation and arrangements--reflected the tensions and problems of living in New York City’s poorest neighborhoods. The leaders in this genre were the Fania record label, which was founded by a former lawyer and cop from Brooklyn, Jerry Masucchi, and a Dominican musician who grew up in Mott Haven, Johnny Pacheco.

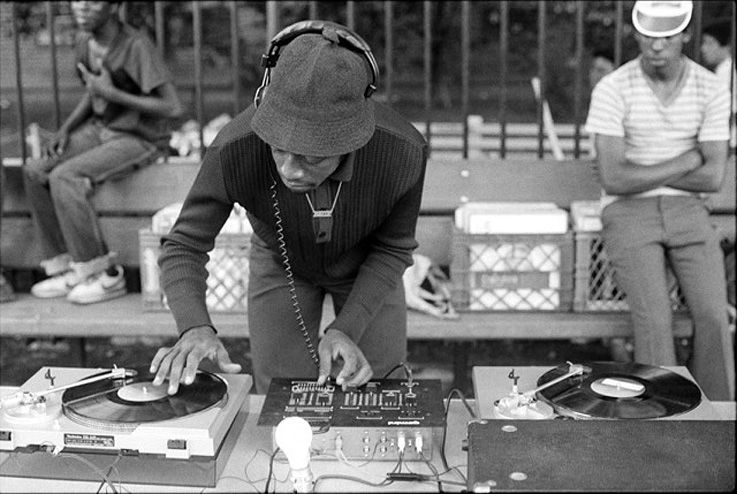

Amidst all the social and economic problems, a musical genre was born here: hip hop. The Puerto Rican, Black, Jamaican and other Afro-Caribbean communities all influenced the different threads of hip hop culture. DJ Kool Herc from Jamaica played his “breakbeats” spinning with MC Coke La Rock, who rapped in the style of the Jamaican sound system toasts. Grandmaster Flash (of Barbadian descent) was another pioneer with his group the Furious Five. He and his assistant, Grand Wizzard Theodore, created and refined “scratching.” The Bronx River Houses were now the home of DJ Afrika Bambaataa, who made major contributions to hip hop. Where mambo music had its home in the dancehalls and clubs, now that these places were gone, hip hop was born and performed in the streets.

*Photo credit: Henry Chalfant

The 21st century has seen major demographic shifts in the Bronx. Puerto Ricans were the largest Latino community there for years but now the Dominican community have passed them in numbers. The large Dominican population has led to the development of an urban style of bachata, made popular by Bronx musicians Henry Santos of Aventura and his cousin, Romeo Santos—who is so popular he played to two sold-out shows at Yankee Stadium in 2014. The borough also has large enclaves of Gambians and Ghanaians from Africa and Bengali communities in Parkchester and the NW Bronx. The largest Garifuna population outside of Central America also makes its home in the Bronx. All of the musicians from these communities have contributed to a new and diverse Bronx soundscape.

*Photo Credit: Elena Martinez

All Rights Reserved | Bronx Music Hall